Marketing is a process used by companies nationwide formulated to encourage the consumption of a company’s products. Like everything else in the world marketing and advertising has its own rules and regulations. Especially surrounding children as they are seen as some of the most vulnerable in society therefore marketing to children has been a subject of debate on many occasions, particularly in the food and beverage industry. A number of companies come under substantial investigation for allegedly contributing to a ‘obesity pandemic’. This transforms further debate about how marketing influences children’s health and diet.

Australia has one of the highest rates of childhood obesity in the world according to the Australian Department of Health. “Approximately 1 in 4 Australian children aged 7-15 are to be considered overweight or obese.’ (Cowper, 2015) Therefore there is an even higher focus on making sure advertising does not breach any codes relating to children. Australia currently has a set of regulatory and self regulatory arrangements which governs the promotion of products to children, of which aims to ensure that marketers and advertisers accordingly develop and maintain a high sense of social responsibility in marketing and advertising food and beverages to children. According to AANA a child is defined as a person 14 years of age or younger. (Australian Association of National Advertisers, 2012)

The Legalities of Marketing and Advertising

The Australian Consumer Law (ACL) is a national law which protects consumers and ensures the continuation of fair trading in Australia. The ACL falls under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 which applies generally to advertising in particular. Which include prohibitions on misleading and deceptive conduct and on making false representations.

For marketing, statutory regulations are based on a multitude of laws. These laws usually cover the media, marketing, advertising, broadcasting, communications, competition, trade, food and/or consumer protection. Designed to regulate content and extent of marketing implementations through guidelines or restrictions. Self-regulations are put into place by a self-regulatory system whereby the company actively participates in, and is responsible for, its own regulation.

What are regulations? The term “regulation” is broadly defined as any law, statute, guideline or code of practice issued by any level of government or self-regulatory organization (SRO).

Regulations can be divided into two categories:

- Statutory regulations – defined by Cambridge Dictionary as “the process of checking by a government organisation that a business is following official rules” this includes further broad concepts mandated by legislation.

- Non-statutory regulations or self regulations – have the same purpose as statutory regulations, but are not enshrined in, or mandated by, law.

The Case

McDonalds is a signatory of the Quick Service Restaurant (QSR) . Other signatories include; Chicken Treat, Hungry Jack’s Australia, KFC, McDonald’s Australia, Oporto, Pizza Hut, Red Rooster. (Cowper, 2015) these signatories agreed to uphold that “the advertising or marketing communication references, are in the context of a healthy lifestyle, designed to appeal to the intended audience through messaging that encourages good dietary habits and physical activity.”(Cowper, 2015) The Obesity Policy Coalition (OPC) submits that the advertisement; McDonalds Happy Studio app breaches the QSR Initiative for Responsible Advertising and Marketing to Children.” (Loh, 2019)

The breach of the QSR initiative falls under “Advertising to Children Code 2.07 under Parental Authority” with subpoints QSR – 1.1 – Advertising and Marketing Message must comply and QSR – 1.3 – Products in Interactive Games. The code has been adopted by the Australian Association of National Advertisers (AANA) as part of the advertising and marketing self regulation. The object of this Code is to ensure that advertisers and marketers again develop and maintain a high sense of social responsibility. This Code is accompanied by a Practice Note which has been developed by the AANA. The Practice note provides guidance to advertisers as well as complainants, and must be applied by the Ad Standards Community Panel in making its determinations. In the event of any ambiguity the provisions of the Code prevail.

The OPC specifically mentions the McDonald’s Happy Studio app, claiming on two accounts that it directly targets children and holds an appeal for children to urge their parents to purchase unhealthy food for them. Part of the process of enforcing marketing regulations is deciding whether or not a marketing campaign is actually directed at children. Making this assessment is not always a straightforward matter; a television advertisement, for example, could be directed at parents rather than at children however this still has an impact on the child therefore marketing to children regulations still apply.

According to Rhonda Jolly the app can be considered an Advergame because “Advergames are advertiser-sponsored video games which embed brand messages in colourful, fun, fast-paced adventures which are created by companies for the explicit purpose of promoting their brands” (Jolly,2011) which is exactly what the app aims to do. It contains a string of activities and games designed for kids to, according to its Google Play description, “develop useful new skills”.

The OPC also takes issue with encouraging children to purchase McDonald’s Happy Meals in order to unlock further functions and levels within the app. “The app includes a call to action for children to ‘Scan your toy’, referring to the toy provided with the Happy Meal that encourages children to buy or convince their parents to buy Happy Meals in order to unlock the extra content.” Subsequently in its defence, McDonald’s raises that the app “only promotes the healthier options of the Happy Meal,” mentioning that the activities and a virtual mask’s in the app feature fruits and vegetables. McDonald’s argued that children do not need to purchase Happy Meals in order to experience as well as participate in the app to its “fullest potential” – stating that other items other than McDonalds toys can be scanned to unlock further levels as well.

The Determination

The Panel determined that even though the app featured foods that would be “considered by most members of the community to be good dietary choices” and included advice to “balance your play with physical activity everyday,” the app was still “directed primarily to children”. However, the panel did side with McDonald’s in finding that the app did not encourage children to “urge parents to buy a product”.

McDonald’s reluctantly obliged to the Panel’s determination and further removed the app from the iOS and google playApp Store. A new and updated version has since been released, amended to comply with Ad Standards’ determination.

McDondald’s walked away this time legally unscathed. If McDonalds failed to comply with the obligations of determination by the panel, it could have resulted in enforcement action by the relevant regulatory authority which could result in litigation, penalties, and adverse publicity.

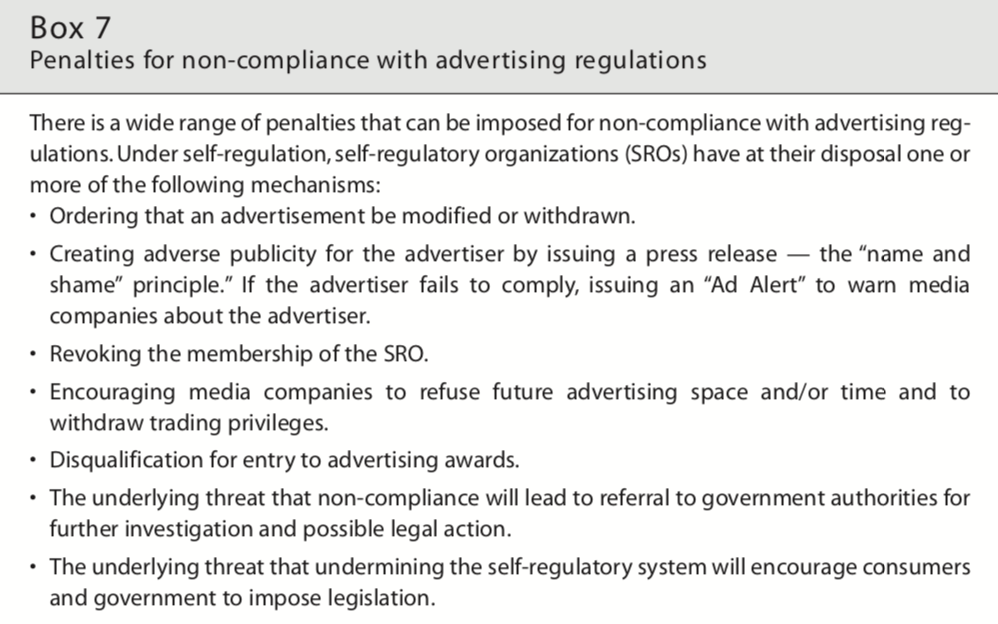

Below is a list compiled by Corinna Hawkes stating further repercussions that can result from advertising on non-compliance grounds –

In Summary

Because of the internet and fast developing media there is an ever changing opportunity for advertising to take new forms other than tv ads. As confirmed by The Australian Government “Children have high levels of consumption and considerable influence on family spending. Advertising and marketing targets them directly from an increasingly young age.” (Australian Law Reform Commission, 2010) In summary, the onus is on the advertiser, is this case McDonalds, to ensure that any advertising or marketing materials do not undermine the authority, responsibility or judgment of parents or carers, nor must such material urge a child’s parents or carers to buy a product for them. Advertisers should always think with a moral compass, understanding the consequences on the influence it can have on children and their families. Ethics can become a grey area in marketing and advertising so legal parameters are essential in the industry.

References:

-Australian Association of National Advertisers, 2012. Viewed 25 April 2020

-Australian Law Reform Commission 2010, ‘Advertising’. Viewed 30 April 2020

-Cowper. A, 2015, Marketing and Advertising Food to Children in Australia. Viewed 1 May 2020. https://www.twobirds.com/en/news/articles/2015/global/food-law-digest–3rd-edition–2015/marketing-and-advertising-food-to-children-in-australia

-Hawkes. C, 2004, p18, ‘Marketing Food to Children: The Global Regulatory Environment’, World Health Organisation. Viewed 30 April 2020

-Jolly R, 2011, ‘Marketing obesity? Junk food, Advertising and Kids.’ Parliament of Australia. Viewed 2 April 2020

-Loh, J 2019, ‘Ad standards cases of 2019- accusations and brands cross the line’, Marketing Magazine. Viewed 25 April 2020